Cor ad cor loquitur ("Heart speaks to heart") -- motto of Cardinal Newman

In celebration of Valentine’s Day and Cardinal Newman’s birthday (February 21) we pay homage this month to Newman and his love of books by featuring three volumes in our collection which once belonged to the famed theologian, novelist, priest, poet, cardinal, saint, and bibliophile. Newman was a well-known book enthusiast, and these volumes must have had a particular place in his affection, although they bear evidence that he gave them away in an act of generosity and friendship.

These massive volumes were already more than a century old when Newman acquired them. They contain the 1698 Paris printing, in Greek and Latin, of the works of Saint Athanasius, edited by Bernard de Montfaucon (1655-1741) a member of the Benedictine congregation of St. Maur. In the 17th century the Maurists were a center of intense scholarly and literary activity. Montfaucon was a prolific scholar best remembered for editions of the Church Fathers such as this one, and for his ground-breaking work in the field of Greek paleography.

Newman, of course, would have known all that, as his own scholarship often focused on Saint Athanasius, the 4th-century bishop of Alexandria, generally regarded as the most important of the Greek Fathers. Newman published translations of Athanasius’ writings in 1843 and again in the 1880s. But beyond his scholarly interest, Newman felt a more personal connection to the Egyptian bishop, and mentions him many times in his letters and publications. The controversies of Athanasius’ day mirrored to some extent those of Newman’s. As the outspoken opponent of Arianism, and the author of important theological treatises on the nature of Christ, Athanasius endured false accusations from his own clergy and lengthy periods of exile from his diocese. Newman also suffered for his convictions; after his conversion he was shunned by many of his Anglican friends and family, and was scarcely treated better by Catholics who too often viewed his conversion with suspicion or merely exploited his celebrity status.

The writings of Athanasius and other Church Fathers were to prove the greatest inducement to Newman’s conversion. His decision to become a Catholic was formed, over many years, from careful study of the Church Fathers and reading of church history, and hardly at all from the influence of contemporary Roman Catholics. As an Anglican clergyman, Newman had minimal contact with Catholics prior to his conversion, but books provided the vehicle for his intellectual journey towards the Roman Church, and books were central to his life thereafter. Concerned about the Anglican bishops’ hostility to his published tracts, he joked about a possible eviction from Littlemore: “Where am I to stow all my books?” he asks in a letter to J. R. Hope (Dec. 23, 1841). Judging by his room in the Birmingham Oratory, this would have been a perennial worry.

Later in life he wrote to Pusey of the renewed kinship he felt for the books of the Fathers, once he had become a Catholic:

I recollect well what an outcast I seemed to myself, when I took down from the shelves of my library the volumes of St. Athanasius or St. Basil, and set myself to study them; and how, on the contrary, when at length I was brought into Catholic communion, I kissed them with delight, with a feeling that in them I had more than all that I had lost; and, as though I were directly addressing the glorious saints, who bequeathed them to the Church, how I said to the inanimate pages, ‘You are now mine, and I am now yours, beyond any mistake.’ (A Letter to the Rev. E. B. Pusey, D.D. on his recent Eirenicon)

The volumes of Athanasius in our collection were given away by Newman seven years before his conversion, and thus may have escaped their owner’s osculatory exuberance. Whether Newman spoke to these pages, we cannot tell, nor have we found any annotations on them, so it is likely that he had access to other copies of the work, which he cites in his 1842 publication Select Treatises of St Athanasius in Controversy with the Arians. But it is inspiring to think of Newman “taking down” these hefty volumes from his shelves; the set weighs some 27 pounds and would have provided him ample exercise.

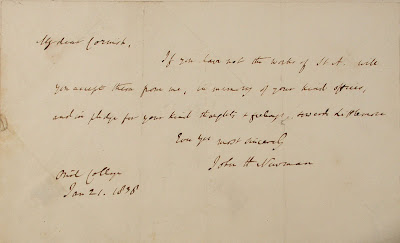

Their original 17th-century French bindings are now quite worn, but internally the set is in fine condition and the front pastedown of Volume I bears Newman’s note presenting the books to his friend:

My dear Cornish,

If you have not the works of St A. will

you accept them from me, in memory of your kind offices,

and in pledge for your kind thoughts & feelings towards Littlemore.

Ever yrs most sincerely

John H Newman

Oriel College

Jan 21. 1838

In January of 1838, Newman was at the height of his career, with a punishing schedule to match; he was fellow of Oriel College, editor of the British Critic, and the principal author of Tracts for the Times. He was soon to publish his Lectures on the Doctrine of Justification. He had built a chapel at Littlemore and was vicar of St. Mary’s, in Oxford, where he was regarded as a spellbinding preacher, and a magnetic influence on undergraduates.

Charles Lewis Cornish (1809-1870), the recipient of these volumes, was then a fellow of Exeter College, Oxford and frequently assisted Newman in Anglican services at St Mary’s and Littlemore. The church at Littlemore is just under three miles from Newman’s residence in Oriel College, and we know from his diaries that he often walked there in company with Cornish and others in the circle of young Anglican Oxonians who were grappling with questions of the modern church and their place in it. Cornish, who co-authored a translation of some of Augustine’s writings, was associated with the Oxford Movement, becoming curate of Littlemore in 1846. Like many of Newman’s young University friends, Cornish, though he remained an Anglican, never forgot his mentor, and on his deathbed asked to have read to him one of Newman’s sermons. A year later Newman acknowledged Cornish in the dedication to the 1871 re-issue of his Oxford University Sermons.

By the time he was middle-aged, Newman had lost many of his friends to death, a fact which made him feel prematurely old. Additionally, most of the portraits of Newman, produced after he had achieved some fame, date from late in his life. All this reinforces the modern tendency, perhaps more pronounced in Catholic circles, to think of Newman as frail and elderly. It is well to balance that picture with the evidence of extraordinary energy, tenacity, and youthful resilience which is reflected in his writing, a prose as vigorous, unaffected, direct and stylistically masterful as any in the English language.

A Book Worth Kissing - Now in Paperback!

William Charles Ross’ 1845 portrait of Newman, painted in the year of his conversion, is one of a handful of images which counter the octogenarian stereotype. A detail from this youthful portrait appears on the cover of Sheridan Gilley’s Newman and his Age, published by Darton, Longman and Todd, Ltd. (1990, Paperback 2003) This acclaimed biography is perhaps the most readable life of Newman, a moving and balanced portrait, full of humor and written in a lucid prose befitting its subject. The book is somewhat difficult to obtain in the U.S. but the effort of doing so is amply repaid.

Image sources:

Photographs of Montfaucon's Athanasii .. Opera Omnia, (Rare Books Folio BR65.A44 1698)

Newman's Room in the Birmingham Oratory (Wikipedia)

Cover from Newman and his Age with detail from Watercolor Portrait of John Henry Newman by William Charles Ross. The original is in Keble College, Oxford.

A great treasure and a great post.

ReplyDeleteI hope at some stage you are able to have the funds to restore the bindings.